When you’re looking at dividend-paying stocks, mutual funds, or ETFs, you want to be selective because, historically, it’s not the highest payers that have performed the best. And when investors reach for yield and buy those highest payers, they tend to invite avoidable problems into their portfolio. There’s a difference between the dividend-centric investor who seeks to buy above-average yields compared to the one who looks to buy to fund a certain lifestyle—because they “need” the money.

Despite the easy appeal of piling into the highest-yielding dividend fund possible when the Fed cuts rates on bonds, there are drawbacks. Jason Zweig reports in The Wall Street Journal:

Although funds with big payouts sound safe, high income can lead to a poor outcome. You need to guard against needless tax bills, overexposure to narrow segments of the market and the chance of deep long-term losses.

The appeal is obvious: Because dividend funds pay out high current income, typically monthly, they can be somewhat less risky than the overall market. Unlike the typical interest payments from bonds, dividends can grow over time, helping hedge against inflation.

And, during the long period of near-zero interest rates that began in 2008, many investors got used to the notion that stocks can generate higher income than bonds. (That was, in fact, the historical norm until the late 1950s.)

To see the potential downside of these funds, though, consider Global X SuperDividend, an ETF with $784 million in assets.

It yields nearly 11%.

That’s huge compared to the income returns of roughly 1.3% on the S&P 500, 2.1% on the Dow Jones Industrial Average and 5% on short-term U.S. Treasurys.

The SuperDividend fund’s supersized yield comes at a cost. Launched in June 2011 at $75, this week the shares traded around $22. That’s a 70% decline.

If you’d bought the ETF at its inception and held continuously through the end of August, you’d have lost 9%—after accounting for all those jumbo dividends along the way. Although the fund slightly outperformed its own benchmark of high-yielding companies, it lagged far behind global small and midsize stocks as a whole.

With such a fund, says Rob Isbitts, a retired financial adviser who blogs about investing, “you’re just paying yourself that high yield with your own money.”

The simple reason: A company that pays a steady stream of growing dividends is probably in robust financial health, but one that pays gigantic dividends is probably struggling and may be desperate to attract investors. Put a bunch of those into an ETF, and you get lots of income but even more risk.

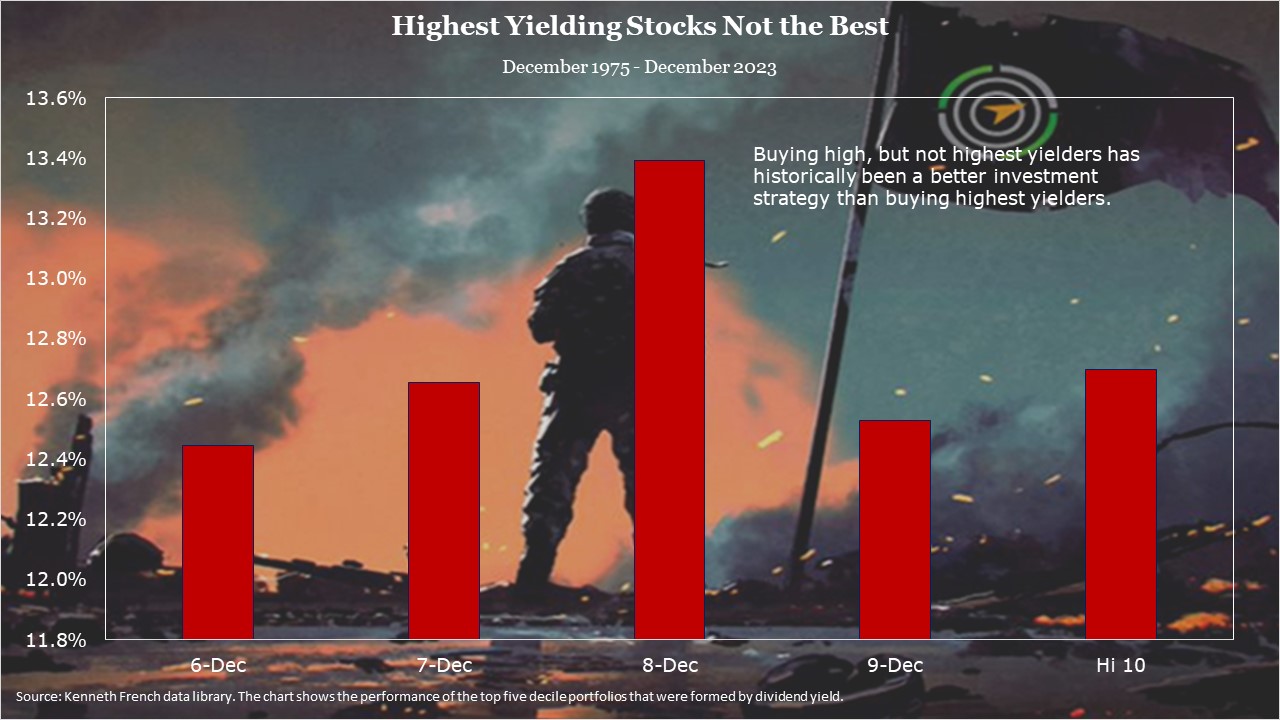

Remember, the calculation for dividend yield is dividend/price. The dividend can remain steady, and the price can drop, leading to a dividend yield that looks appealing. The price drop, however, may portend a bad future for the company whose stock is in question. In the chart below, you can see that companies with the highest dividends (those in the ninth and tenth deciles of the market by yield) underperformed those in the eighth decile since 1975.

Action Line: Be careful when reaching out for yield; your hand might find empty air. Perhaps it’s more important to focus on companies with a history of increasing yields and the intent to raise them further, backed by a strong balance sheet. When you want to talk about dividends in your portfolio, I’m here. In the meantime, please click here to subscribe to my free monthly Survive & Thrive letter.

Originally posted on Your Survival Guy.