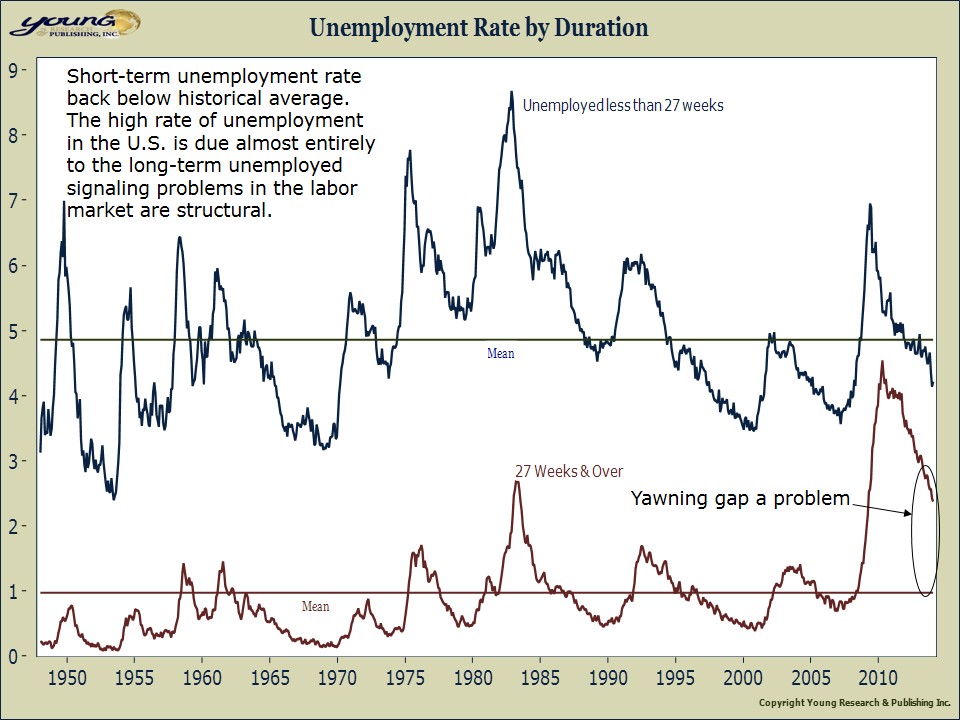

On February 15, Barron’s ran what many economists (especially those at the Federal Reserve) would consider a provocative piece on the labor market. Barron’s reporter Kopin Tan points out for readers that the labor market may be tighter than many economists are presuming. At Young Research we’ve long held the view that a meaningful portion of the high unemployment rate is structural. Structural unemployment is a problem, but not one that can be remedied with short-term stimulus. If you are a Barron’s subscriber the article is well worth a thorough read. Below are the highlights with the chart to illustrate the point made in the text.

The prevailing wisdom suggests help is needed until we can generate enough Help Wanted ads. But if wages were to start climbing with the mercury — yes, even this winter shall pass, that groundhog be damned — how long can our central bank justify zero interest rates?

Already, our jobless rate has shrunk to 6.6% from 10% in four years, but even that masks the improvement within. Among Americans who want a job but who can’t get one, 36% have been unemployed for more than 27 weeks. These “long term unemployed” are a chronic challenge: Unemployment among this cohort remains at an elevated 2.5%, higher than peaks seen in prior recessions, and much worse than the 50-year average of 1.1%, notes Anthony Wile, a JPMorgan Funds analyst. But while they keep the overall jobless rate high, the long-term unemployed lack bargaining power with prospective employers, and so exert little pressure on wages.

In contrast, the short-term jobless rate — among Americans momentarily out of a job and scrambling to find one — has far greater influence on wages. This has continued to tighten to 4.2%, falling below highs suffered during previous recessions and already healthier than the 50-year average of 5%, Wile notes. If this keeps up, it’s just a matter of time before wages rise.