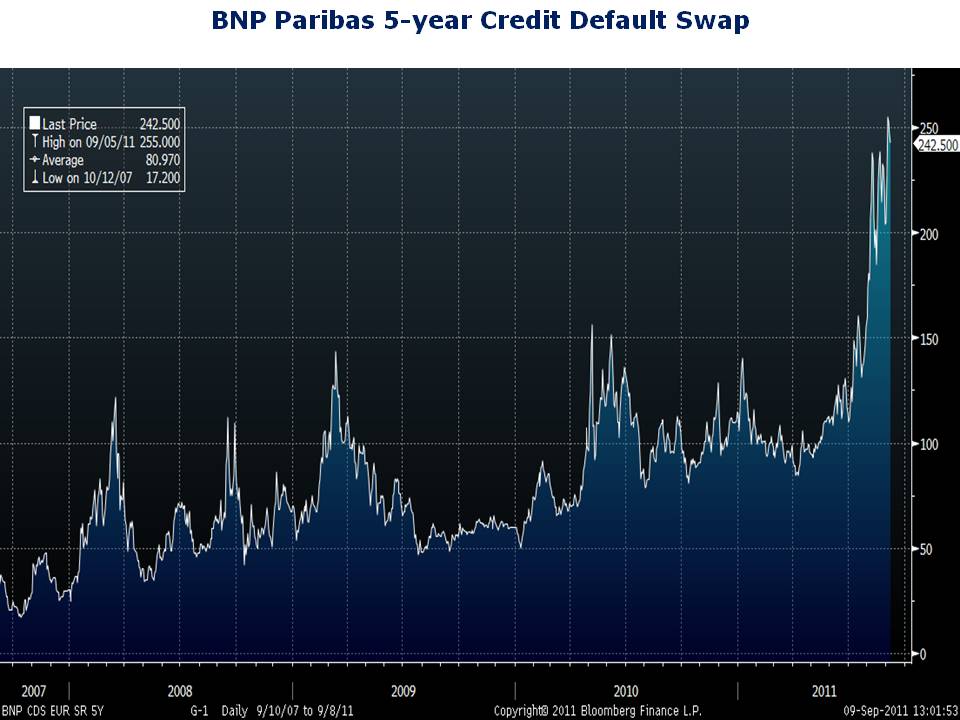

You really have to be careful what you read these days. There is loads of misguided advice pumped out of the financial press. I recently came across an article in one of the leading personal finance magazines that offered especially appalling advice. The article was about money funds and whether or not they are safe given the euro area’s sovereign debt and banking crisis. What does the euro area have to do with U.S. money funds? According to Fitch Ratings, prime U.S. money funds have almost 50% of their assets invested in European financial institutions. Not such a comforting thought when you look at charts like the one included below. This is a chart of the five-year credit default swap (CDS) for BNP Paribas, France’s largest bank. A credit default swap is like a life insurance policy for a company. Buyers of CDSs are like the beneficiaries on the policy. If the underlying company defaults (dies), the buyer gets a payout.

As with life insurance policies, companies at greater risk of death pay a higher premium, which is reflected in the price of the CDS. But unlike life insurance policies, CDSs are bought and sold every day. Changing CDS prices tell investors if a company’s risk of default is rising or falling. Falling CDS prices signal lower risk of default, while rising spreads signal greater risk of default. So in CDS land, up is bad and down is good.

Looking back at the BNP Paribas chart, there is cause for concern. The five-year CDS on BNP Paribas is near record-highs. Investors are more concerned about the risk of default at France’s largest bank than they were at the height of the financial crisis. Given the large stake that prime money funds have in euro-area financial institutions, this leading personal finance magazine I referred to above asks if investors should worry about their money fund breaking the buck.

So, should you worry about money funds breaking the buck? Not according to the article. Why not? Because, says the article, “the trillions of dollars and millions of investors in money funds invite government intervention if it becomes necessary.” In fact, the author cites a Fitch Ratings analyst who says that money fund managers are flocking to the largest and strongest European financial institutions.

No wonder Main Street holds Wall Street in such low regard. Many on Wall Street are freeloaders. The Street advises investors to stick with their prime money funds because they are too big to fail. At least too-big-to-fail banks pay deposit insurance. Money funds have the implied backing of the government but pay nothing to fund such a backstop. Haven’t we seen this movie in Fannie and Freddie, and yes, the money market industry, before?

What I find most discouraging about the advice to hold prime money funds is the failure to recognize the unfavorable risk-reward trade-off. The average yield on a prime money fund is .01%—that’s one basis point. Compound that annually and it will take you only 100 years to earn 1%. You could do better by recycling aluminum cans. And you can earn the same return in a money fund that invests in full faith and credit U.S. Treasury securities or one that invests in treasuries and agencies. Why take the added risk for no additional return? The only winner when you invest in a prime money fund today is the freeloading fund sponsor.