In September, Warren Buffett announced that the Berkshire Hathaway board authorized a multibillion-dollar share-buyback program. Berkshire shares soared as much as 12% on the news. The market’s reaction to the buyback announcement is common. When companies announce buyback plans, their stocks often get a pop. But are the gains justified? This question is more important today than it has been in years past. Over the last decade, share buybacks have become the preferred method of returning cash to shareholders. In 2006 and 2007, U.S. companies bought back more in stock than they paid in dividends. And in the second quarter of this year, U.S. companies repurchased $475 billion (at an annual rate) worth of stock—the most since just before Lehman Brothers collapsed.

One reason stocks get a lift when buybacks are announced is because investors assume the announcement indicates that a stock is undervalued. The theory is that management knows the business better than anybody else and if management is accumulating shares, the stock must be cheap. But when is the last time you heard a CEO tell investors that his company’s stock was overvalued? Company management almost always believes their stock is undervalued. Management has skin in the game. CEOs are judged on the performance of their firm’s share price, and most are awarded options that increase in value when the stock price rises. Buying back shares helps lift earnings and levitate the stock price, which of course increases the value of management’s stock options.

Buyback announcements can also mislead investors. When a company announces a stock buyback plan, shareholders often assume their claim on the company will rise as the share count falls. But for some companies, buybacks are used to mop up shares issued to executives through an employee stock option program. This type of activity is common in the technology industry. Take software company Oracle for example. Over the last two years, Oracle spent $2.7 billion buying back shares, while simultaneously issuing $2.5 billion worth of stock to employees. The net result: shares outstanding rose 1.7%. Oracle’s $2.7 billion in buybacks were nothing more than an unreported expense to existing shareholders.

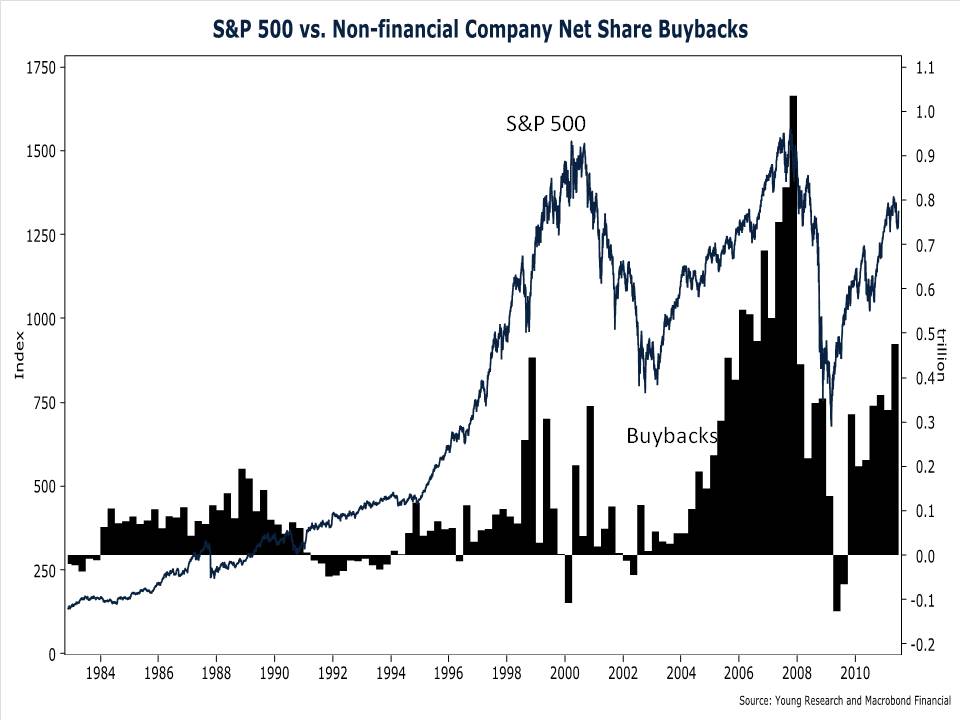

The most important shortcoming of stock buybacks is that they suffer from poor timing. Buyback activity tends to peak at the top of the business cycle when companies are flush with cash and stocks are reaching new highs. Then, when the cycle turns and share prices tumble, companies hoard cash, or worse, issue shares. You can see evidence of this behavior in my chart below. The chart compares the value of share buybacks to the S&P 500. Companies ramp up buyback activity when share prices are peaking, and cut back when they should be buying the most. As a recent Fortune article pointed out, long-time Citigroup shareholders should be familiar with this value-destroying strategy. Over the last decade, Citi spent $31 billion buying back stock—and then, after a 97% plunge in the stock price, the company raised billions in new equity. Existing shareholders were effectively wiped out through dilution.

For my money, dividends trump buybacks as a means of returning cash to shareholders. Dividends are consistent and reliable. Buybacks put too much discretion in the hands of conflict-ridden management teams that have a history of overpaying for shares. That is not to say that all buyback programs are poorly executed. Buffet’s rules-based buyback (where shares can only be repurchased at less than 1.1X book value) is a clever way to take the discretion out of a buyback program, but Buffett’s approach is the exception, not the norm. Stick with companies that favor dividends over buybacks.